"Readers of RADIO TIMES may be puzzled by the recent article (Jan 16) 'Keeping Faith with the Viewer.' For many people who work in television it is also very disturbing. Because beneath its bland, sweet reasonableness, which is the house-style of BBC bureaucracy, there is a warning.

The warning is this: if you refuse to take our gentlemanly hints, we shall censor or ban any of your programmes which deal in social and political attitudes not acceptable to us. The odd rebel may be allowed to kick over the traces, occasionally. Provided this is an isolated event, and not part of a general movement, it only helps us to preserve our liberal and independent image. But enough is enough.

The important thing for the viewers to understand is that this is an argument about content, not about form. We are told that 'what he sees must be true to fact or true to art' but there is no acknowledgement of the fact that the screen is full of news, public affairs programmes and documentaries, all delivered with the portentous authority of the BBC and riddled with argument and opinion. It is a question of which argument and what opinion. Some are acceptable; some are not.

And the gloves are really coming off in the traditionally safe area of drama. Why? If we go back to our article we are told that it is a question of the techniques used, the conventions established. 'Throuh a different set of conventions the viewer knows ... that this kind of programme (drama) will not be a photographic record of real events. It will be art presented as art.'

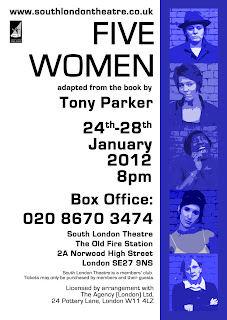

Over eighteen months ago a Wednesday Play called Five Women was completed. Everyone who has seen it (a very privileged few because the BBC won't allow viewings of material that it bans - despite a written request from twenty-five writers, directors and producers) agrees that its artistic merit is beyond doubt. But it used actresses to tell the stories of women who had been in prison. Used them so convincingly, that despite the end credits to artists, and front titles identifying it as a Wednesday Play by an author and a RADIO TIMES billing doing both, the BBC decided that viewers might be misled into thinking it was real! And worse, that the style might be imitated until viewers wouldn't know whether to believe even the News (good point: should viewers believe the News?)

The BBC has never given a clear reason for banning this show. After more than twelve months of conversations and correspondence with the BBC, the writer, the director and the producer are still mystified. Was it the form, were the actresses just too convincing (but what else do we ask of art?) or was it the possible uses to which this approach might be put?

What is clear is that the objection to mixed forms is only introduced when the content is found offensive by our guardians. Much humdrum television drama contains some example of 'real events' in the use of stock film and sound effects. In fact the BBC regularly exploits so-called fiction as a matter of policy - the Archers constantly peddle hints to farmers from the Ministry of Agriculture and it is, after all, some years since listeners sent wreaths to Grace Archer's funeral. When Till Death Us Do Part filmed Alf Garnett and his son-in-law in the middle of a real football crowd no-one in the BBC was worried that this was not keeping faith with the viewer.

A documentary called Hit, Suddenly, Hit was also banned last autumn - again with no public explanation. Its form was conventional but its argument was not. It contained people like Marcuse, Erich Fromm, Stokeley Carmichael, Allen Ginsberg and Adrian Mitchell. The BBC found it 'unbalanced.' So it's not just form. It appears that the poor viewer shall only be selectively protected - and the areas selected are sensitive ones where social and political assumptions might be upset. This is spelled out almost innocently in the finger-wagging pay off to "Keeping Faith with the Viewer.'

'In the history of protest about broadcasting trouble' (ah, yes, trouble) 'has most frequently been caused when the audience got - not what it did not want - but what it did not expect.' Are the quietists not aware that the worst thing about most television is that you get exactly what you expect? It is as predictable as the grave.

Tony Garnett, Jim Allen, Roy Battersby, Clive Goodwin, Ken Loach, James MacTaggart, Roger Smith, Kenith Trodd, London, W8"