It occurred to me that a good way to really understand Tony Parker and the way he worked would be to put on a play based on one of his books. I belong to an excellent local theatre club, and enjoy the repetitive reading that is required in the production of a play. Parker’s emergence into the public domain was also through a kind of public performance. His conversations with Robert Allerton (a man he had met through voluntary work as a prison visitor in the 1950s) were taken up by Paul Stephenson, BBC Talks Producer, and turned into a radio programme. It was this performance that set the scene and propelled Parker towards his status as an extraordinary writer, and to earn him the accolade of oral historian.

Five Women is Parker’s fourth book, published in 1965 and was turned into a BBC Play for Today by Director Roy Battersby and Producer Tony Garnett. Battersby had hoped to make a drama based on Parker’s second book, The Unknown Citizen, which came out in 1963, but when he approached the publisher for rights, he discovered they had already gone. He resolved not to lose Five Women, and with the rights secured and a BBC commission in his pocket he began preparations for filming in 1967.

I don’t remember exactly how I chose Five Women for my own project, now in 2011, but it had something to do with the belief that there must be a script around somewhere. A chance encounter in the Theatre Club Bar had prompted me to put my thoughts about the play into words and my congenial interlocutor urged me to alert the Theatre Committee to the prospect of my directing it. Although I still didn’t have the script to submit, the Committee was warm in its response, and so we proceeded in the hope that it would soon materialize.

My enquiries led me to the BFI archive where a 16mm copy of the televised play is carefully kept in case people like me want to watch it. They had other scripts by Parker (in fact he went on to write 172 TV scripts!), but not this one. Julian Petley is Professor of Screen Media and Journalism at Brunel University, and as luck would have it was in the office and able to take my call – I knew him from some years ago when I also worked at Brunel. He gave me a gentle push in the direction of producer Tony Garnett whose work he had recently been involved in reviving, and this was enough to open the door to Roy Battersby. Both men were willing to discuss their work with Tony Parker (this is quite typical and is witness to the great esteem people still hold Parker in), but the news was unexpected: there is no script. They had improvised the play from the book.

Well, the idea of improvisation at the local theatre club is exciting in principle, but bewildering in practice, and when Battersby went on to describe how the editing process had taken three times longer than expected, I knew I had to stick to the text. I sat down at the keyboard with the book, and found it surprisingly easy to turn the chapters into five wonderful monologues to start us on the process.

As it turned out, however, there are six women in Parker’s book, and four women in the BBC televised play. How does this fit with the title? Battersby had shrugged and suggested there was poetry in the title, then launched into a fascinating story. The film he originally contracted to make did indeed involve five women but the BBC management got cold feet and cancelled the broadcast. They explained this in terms of the blurring of fact and fiction. Here were five actresses speaking the words of real women; the traditional reference points were blurred they said, truth was being messed with. Huw Wheldon was reduced to arguing that if the public watched this and then watched the BBC News, they wouldn’t know whether to believe what they heard. The argument is weak to say the least, but it functioned as a wedge and forced an exchange between artists and managers in the letters page of the Radio Times. Finally the managers conceded – they proposed to cut the play (one woman disappeared completely), and show it at a less popular time.

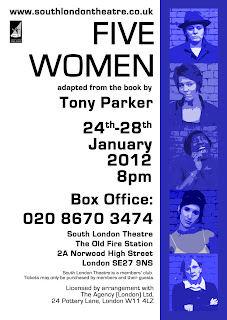

This is how the Five Women became Some Women (broadcast on 27 August 1969), and Joe Bishop (played then by Bella Emberg) hit the cutting room floor. We are reinstating Joe for our production, scheduled for production at the South London Theatre, 24-28 January 2012. Carol Dean, the character Parker chose to open his book with, never even entered the original cast list, and I also found it easy to overlook her in our production. Why do these two women present problems for us? Roy Battersby struggled to find a word to sum up the difficulty the BBC had with Joe Bishop. He said there was a ‘ghastliness’ that the BBC was somehow unable to be associated with.

I think this is an excellent way to begin our exploration of Tony Parker’s work. I’d like to try to sum it up now like this: Parker was someone who dedicated himself to listening to difficult things, and to bearing witness to people who had to endure difficult things. Both through the act of listening and the act of writing, and sometimes through both, he achieved a kind of transformation which made it possible for a truth to be heard, and to be taken in. Surely, this is the mark of an artist.